AMERICAN CEMETERY

John L. Pilker

Service Number 20344946

PFC 175 Infantry 29 Div.

Maryland June 19, 1944

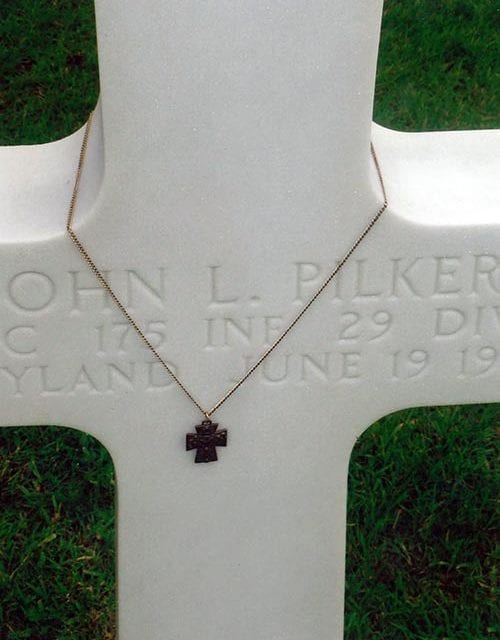

This is the story of the medal that I left hanging on his grave marker at Normandy.

I was drafted into the Army in 1966, when the Vietnam conflict was in full swing. At the time I was working in Chicago at an abrasives manufacturer. Jim Lorrigan worked at the desk immediately behind me. Although I never thought that we had a close friendship, which was not how he felt.

I had to learn about Jim’s life from others, as I never heard him even mention serving in World War II. He was captured during the Battle of the Bulge and became a German prisoner of war. Jim was no doubt suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although I don’t think the term was even in existence at that time, for it was gradually recognized in post-Vietnam era.

Normally quiet and friendly, occasionally you could see a change in him that continued to deteriorate for a week or so as he became short-tempered, argumentative and abrasive. On more than one occasion I overheard one of the management team come to his desk and tell him, “The warehouse is really behind in pulling and shipping orders. Would you mind helping them out for a couple of days until they catch up?”

Jim would then vacate his desk and work in the warehouse for a few days. Without the pressure and stress of the desk job, his demeanor would begin to change and his normal disposition resumed. I have always admired management for how they dealt with his situation, for when he returned to deskwork he was back to normal.

In any case, I was aware that my draft number was getting closer and that I would soon be leaving. That was something that I didn’t talk about, although all of my peers were also aware of the chances a draftee would have in surviving Vietnam.

On my last day, before leaving the company and Chicago to report for the draft, Jim took me aside. With tears streaming down his face, he pressed a bronze medal on a chain into my hand. “Take this and wear it like I did when I was in the war. It will protect you as it did me.” I tried to object, but he was insistent so I took the medal and promised I would return it when I came back after my military obligation was completed. What he gave me was his Saint Christopher medal. It is made of bronze and so worn that the raised figurines were barely visible.

I kept the medal, with full intentions of wearing it while I served in Vietnam. I never went to Vietnam. I never returned to the job in Chicago. Jim died during the intervening years, so I never saw him again.

I still have it over 45 years later. It’s time to return it. I leave it, as a tribute to Jim Lorrigan, on a grave marker chosen at random from the thousands at Normandy. I think Jim would have liked that.

As I left the cemetery and walked across the grounds to depart, a group of youngsters were sitting on the steps of one of the memorials. Some were working together and others individually. I asked one of the teachers what they were doing and she replied, “Poetry.” I then asked if any of them wrote haiku and she answered, “I just had one ask me if they could do haiku.”

I couldn’t resist, I gave her a copy of the following that I had just written about this experience.

American Cemetery at Colleville-Sur-Mer, France

Perfectly aligned

As far as the eye can see

Graves at Normandy

A common blanket

Of green grass, it could be said

Warms each of their beds

All graves face westward

Toward their family and home

As they lie alone

Ten thousand crosses

Ten thousand young men who bled

Lying foot to head

Here a Christian cross

Rests beside a Jewish star

Brothers you still are

Many have a name

Roll call of our nation’s best

Now in final rest

“KNOWN ONLY TO GOD”

Reads the bone-white cross of stone

Unknown, not alone

Now with your brothers

Most of whom you never knew

They wait here with you

Young men in their prime

Gave all that they had to give

So freedom could live

All who lie here ask

Those with and without a name

“Did we die in vain?”

You can imagine her surprise as she said; “I can’t wait to share this with the class.”

I know that in the future my mind and thoughts will return again and again to the American cemetery, for there is too much to be absorbed during one short visit. But I must also add that there is a new peace that I have already found, knowing that Jim’s Saint Christopher medal is in that cemetery instead of in a drawer where it has resided for so many years. At last, I have fulfilled my promise to him, that I would return it after Vietnam. Somehow I feel that I can now say that I kept my promise.

After returning home I researched to see what I could learn about PFC Pilker. He served in the 175th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, 3rd Battalion,

Company K and landed on Omaha Beach June 6, 1944. Records reflect that 620 men from this unit were killed and buried in various cemeteries in this theater.

He was killed June 19th. The 3rd Battalion held a position about three (3) miles from Saint Lo and withstood one major and several minor counter attacks by the Germans. It must have been in one of these attacks that he was killed. He survived less than three weeks combat and was awarded the Purple Heart.

On Memorial Day, to honor John Pilker for his sacrifice, I decided to attempt to locate a family member, who might possibly be interested in the story of the events leading up to my visit to his grave. I found the records of his father and mother and he had one sister, Bessie Pilker who was two years younger. John was single, so he had no family to trace. I found an elderly great niece who knew nothing of an uncle buried in Normandy.

There is where my attempt ended and I must conclude that he is, in all likelihood, not remembered by any of the family. So it appears that his random grave was also a forgotten one. In many respects, that makes the experience even more meaningful to me.

There is one additional coincidence that should be mentioned. John Pilker’s family were of the Catholic faith. There is now a Catholic religious metal hanging on his grave marker.