I grew up in the West Side, a corner of South Bend, IN., where the poor managed to get by. My father spent his mornings driving the back-alleys, rooting through garbage, looking for anything valuable or fixable. Predicting what he might come home with was nearly impossible, and the treasures he found would find their way through the neighborhood. A yellow lamp was sold to Mrs. Elks for a dollar—a half-empty can of Pennzoil was traded to Kenny Gifford for two tomatoes—dad always seemed to find a home for everything. The West Side was a rough life, rough for everyone, but together the babies were raised, the dead were buried, and the garbage trucks ran on Tuesdays.

One blistering Tuesday in July, dad returned from junking with an oddly-shaped green box. It stood out from the junk because it had no scratches, not even dust from the truck seemed to cling to it. “Take this to Rosie,” he said with a smile, “she’s been looking for one of these.” I did as I was told, loading the large green box onto a rolling cart. I hauled the load to Rosie’s where I was greeted by her dog.

Rosie’s dog, an old grey Shepherd mix with a sagging belly, was the friendliest dog I ever met—despite spending its whole life tied to a rock in her front yard. Rosie’s house sat on the corner, a faded yellow shack beneath an enormous oak tree. The back was marked by an outhouse that wafted unmistakable odors down the street. Nobody seemed to care, and anyone who came close enough would be met by Rosie. She liked to talk, and talk, and all her conversations began the same way, “you there, did you meet my dog Shep?” The insistence of her voice assured everyone that she would not be denied, and the conversation would not be short.

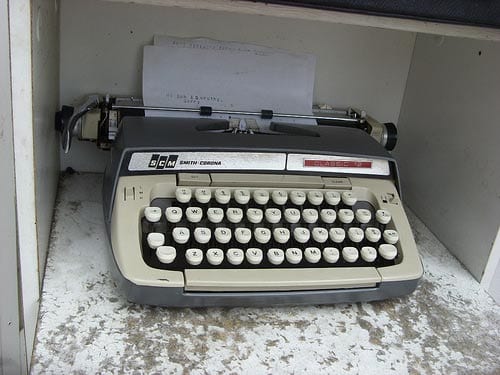

The screen-door hung on its hinges rattling back and forth against the doorframe as I knocked on it. Rosie came to the door, “Ohh Lordy, Ohh Lordy, what have you got there child?” There was an excitement in her eyes, and she didn’t even bother to open the screen-door, she just stepped through the empty frame and loomed over the green box on the cart. She fumbled with the sides for a long minute until at last the top seemed to pop off, revealing a beautiful typewriter. Rosie squealed with happiness, “Ohhh come to mama you beautiful girl.” I thought she was going to hug me, but her arms passed straight to the typewriter, lifting it in one fluid motion, and carrying it inside. She closed the door behind her, and astonishingly, she never said goodbye.

~~~OOO~~~

My husband and I traveled from the East Side to visit my aging parents. The truck my dad used to use for his junking adventures sat rusting in the yard, its hulking frame now supported by cinder blocks and the back was covered by a sagging tarp. Their house still had the same orange shag-carpet, the same wallpaper depicting wooden spoons. Little had changed really, and what did seemed to happen so slowly that it was unnoticeable. When we arrived the mood was sullen. There was something in the air, a sorrow and ache I had not seen in my father’s eyes since Mrs. Elks moved away. “I might as well tell you,” he said softly, “Rosie is on her deathbed, and she won’t let the doctors help her no more.”

I had not seen Rosie for several months. She was 92 years old, and it was hard to imagine the neighborhood without her. The house on the corner was the cornerstone of the neighborhood. Kensington Ave. was not like my East Side neighborhood. Here people knew their neighbors—we knew the kids, the grandkids, the dogs and cats, the cars and jobs, the dinners and the gorgeousness of the mundane. We were a family, and although I had moved away, I was born into the neighborhood. I was a Westsider, and I did what Westsiders do, I visited my neighbor.

I approached Rosie’s door, which had flung itself open with the breeze and clattered against the shack. The windows were open and Kenny Gifford stepped out from his porch several houses down. He yelled up the street, motioning with his arms, “Just go in. Go on in. She’s not coming to the door, April, just go in.” I understood the situation and stepped through the door, pausing only for a moment to look at the old rock where Shep used to be tied. “Rosie, it’s me April, I came to see how you’re doing.”

There were only two rooms in Rosie’s house, she was in the bedroom, spread out on the bed with one red slipper dangling from her foot. The bed seemed to be the only place in the room that was not covered in clutter—there were stacks of bundled papers everywhere. I approached the bed and I knew she was already gone. She looked like a stranger to me, the way her mouth pulled back without her false teeth. “Ohh Rosie, I’m sorry I came too late to say goodbye.” I sat on the edge of her bed, and cried like a baby for several minutes until my cries turned into an aching lump in my throat, which faded into an empty place in my heart.

I took a good look around the house before I left. I wanted to remember her house, maybe wash away the sight of her laying there—I wanted to remember how she lived. I noticed the bundled stacks of paper that filled the bedroom were typed. She must have used that old green typewriter every day since she got it. She left a sheet in the roller which read, “I don’t see no way around this fact. There ain’t no way I can write the last line myself.”